Opportunity areas Part 2: 'There for the taking' - (Re)writing gentrification & placemaking

Confidence, Nicole Mollet, 2016

This is part two of a three-part series of posts about Opportunity Areas. Part one is here.

Part two explores Sarah Butler’s work in a little more detail. Creative consultations, writing stories for Creative People and Places, advocacy of socially engaged writing as part of regeneration agendas, poetry hoardings ‘covering’ demolished social housing sites whilst new builds spring up and working for the New Deal for Communities. It reveals, perhaps, how artists can be increasingly drawn into complicit relationships with local councils, the state, funders, charities, schools and property developers. It is part of an ongoing piece of research into why the once shunned practice of socially engaged art became so fashionable, so enticing, so ‘useful’ and about how, I argue, it is being used to promote gentrification and hoodwink local people into believing they have a voice whilst their words and homes, their thoughts and neighbours, are twisted, polished and cleaned away as if they were inconvenient stains. But can the ‘stains’ (read: everyday people and everyday lives) on our heartlands ever be removed? Mediation is such a tricky game – a consultant’s game – that always, to one extent or another, silences the very people it (falsely) claims to represent. Do artists need to think twice before rushing to aesthetically cleanse the imperialistic advance of neoliberalism and to artwash social cleansing on behalf of greedy, heartless property developers and cash-strapped local councils desperate to dispose of public land and the people who live there, who deserve to stay put, to stay in their families, homes and communities?

ARTWASH…

People, Nicole Mollet, 2016

Sarah Butler is a novelist and a ‘writer and literature activist’ who also produces ‘socially engaged, place-specific writing’ (2016h). In 2008, she described urban renewal and regeneration as a ‘complex process’ that offered writers willing to ‘effect real change’ by contributing to ‘successful place-making’; opportunities were, she said, ‘there for the taking’ (Butler, 2008, p. 44). Butler is particularly interesting not only because she is both a writer and a consultant but also because, as well as being involved in the socially engaged art ‘interventions’ around Elephant and Castle which were discussed in part one of this three-part series of posts, she is currently working for Creative People and Places[1] and previously worked for the Social Housing Arts Network[2] in Bolton in 2015[3] and several other projects in areas undergoing rapid redevelopment. She also presented a paper entitled Writing, Re-writing and Erasure: a consideration of the Heygate Estate, South London at Everywhere and Nowhere: An Interdisciplinary Postgraduate Symposium on Imagined Spaces at the University of Nottingham[4]. I could not access a copy but I would be very interested in reading Butler’s take on the social cleansing of the Heygate. Take a look at Southwark Notes extensive documentation of the process leading to the demolition of a once proud council housing estate.

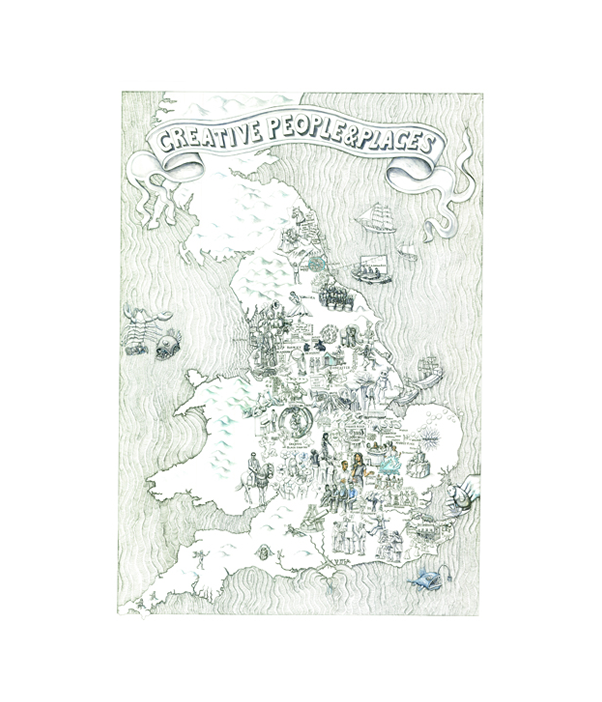

Map, Nicole Mollet, 2016

Together with visual artist Nicole Mollett, Butler is currently working on More Than A Hundred Stories[5]: a commission by Arts Council England ‘to creatively map and respond to … [Creative People and Places] achievements, the problems it faces, and the questions it has generated’ (Butler & Mollett, 2016). It is interesting to note that Mollett’s mapping style is reminiscent of that of early modern New World maps with little ships sailing around the English coast (a new take on artists ‘parachuting in’, perhaps), flags marking places of low engagement (read: previously uncultured enclaves now ‘civilised’), stereotypical local landmarks, and, interestingly, it is as though Europe, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland barely exist - they are certainly either not featured or feature-less on Mollett’s map[6]. Of course, the idea is to map the twenty-one Creative People and Places projects in England but it also invokes (perhaps parodies) the origins of colonialism. I argued recently that Creative People and Places is not about empowering ‘uncultured’ (read: working class, dispossessed, exploited and marginalised) people but actually conspires to further disenfranchise and disempower them in the name of GREAT ART AND CULTURE FOR EVERYONE!

Untitled, Nicole Mollet, 2016

It is interesting to read Butler’s A Place For Words - an Arts Council England funded website – that clearly advocates for creative writers in ‘the regeneration of our towns and cities’, asking: ‘Why would a planner, developer or architect pay a novelist or a poet to work alongside them to inform, animate and critique the process of place-making?’ (Butler, 2016c). Like her other work, the information here does not appear to be about activism but rather about opportunity. There are a number of alternative introductions to the practice, depending upon professional background. The Introduction for Regeneration and Urban Design Professionals, for example, begins by stating: ‘Working with the right writer at the right time and in the right way can make a powerful contribution to the process of making our UK towns and cities better places to live, work and play in’ (Butler, 2016d). Butler outlines how ‘creative writers can work alongside urban design and regeneration professionals, delivering work that engages with and informs the process of planning and developing new communities, and regenerating existing ones’ (ibid.). It is clearly an attempt to sell creative writing as a value-adding activity for urban planners and property developers:

We are passionate about the potential for exciting and innovative work in which writers can work with communities, places, and those driving the change and improvement of places, to facilitate real communication, discover connections, and ultimately contribute to making those places more attractive and desirable places to live, breathe, work and play in (ibid.).

Whilst Butler is quick to add that she does not advocate ‘writers slotting into the role of public-artist’, and proposes writers adopting ‘a social role: to question, to listen, to converse and to articulate’, her primary concern is about ‘well-planned interventions that happen at a time of change’ (ibid.). The language here is vague enough to avoid overt complicity.

Meanwhile, the Introduction for Arts Professionals offers an alternative vision. It starts by situating the work of A Place For Words within the debate around ‘the role of the arts in the process of regeneration, from artists working on design teams, to the place of creative industries and creative skills in the regeneration of place and community’ whilst clearly advocating a greater role for writing in ‘a sector dominated by the visual arts’ (Butler, 2016e). Yet, perhaps the Introduction for Writers offers the most open description of Butler’s ambitions, beginning with the statement: ‘For writers interested in place, people and communities, the field of regeneration offers a wealth of creative and professional opportunities’ (Butler, 2016f). She seeks to ‘to begin to put creative writing on the map’ (ibid.). It would appear that the Creative People and Places map discussed above at least partly achieves this objective.

Another of Butler’s projects, South Kilburn Speaks[7] (2011), ‘a partnership between South Kilburn Neighbourhood Trust and The Poetry School’ (Butler, 2011) was also commissioned by the London Borough of Brent as part of South Kilburn’s public art programme 2010-2011, which was funded by the New Deal for Communities – a notorious New Labour tool that frequently promoted gentrification. I recommend Loretta Lees’ article (2009) about the impact of the New Deal for Communities on the Aylesbury Estate. The project in South Kilburn resulted in poetry hoardings surrounding recently demolished social housing in Kilburn as part of the gentrification of the area[8]. See the South Kilburn Speaks blog here for a better understanding of the project.

It would seem that the notion of ‘creative consultation’ is important to Butler. She describes it as a ‘key aspect of successful regeneration’ (2008, p. 42). She believed that ‘writers are uniquely placed to deliver’ creative consultations because they ‘turn messy, complicated issues into tight forms, dense with meaning’ into powerful representations of ‘the voices of the people directly affected by a process of regeneration’ that can be delivered to the ‘people making the decisions’ (ibid.). This seems to suggest that writers (and perhaps artists) are better placed to talk for or represent people and communities undergoing the ‘slow violence’ of regeneration than the people and communities themselves. Other than the obvious questions relating to choice of form and, of course, to the unavoidable hierarchical nature of the role of writer/ artist as mediator/ communicator, it is worth considering whose words are actually represented by the outputs of creative consultations: the artist’s, the local council’s, the property developer’s, the funder’s, the state’s, or the people? Of course, all of these voices will be melded into these tight, dense outputs, but that also means no one’s voice. Individual comments and complaints are edited at best, homogenised as a default, and completely edited out or misrepresented at worst. They may even, as could be seen in South Kilburn Speaks, be turned into pretty facades, screening gentrification, with screened words.

Art is often keen to claim it can speak for the people better than the people can themselves. But, I argue that, whenever state and corporate money is involved, such attempts always end up representing the voices of the funders and disempower people who may believe that art can make a difference, can save them. Unfortunately, it cannot. Even those with the very best of intentions end up making art that, like the fabled Nero, does nothing more than fiddle whilst Rome burns. For art to be revolutionary, for it to demand radical action for radical change, it must be part of a revolution – a movement of movements, part of radical actions. This cannot be achieved when working for the guardians of the status quo, particularly the artwashing sentinels of neoliberalism.

Part three will be published on Thursday 27th October. The final part. A cautionary tale…

[1] Butler worked on More Than A Hundred Stories (2015-ongoing) alongside artist Nicola Mollett.

[2] This is interesting because the Social Housing Arts Network also worked for Poplar HARCA, commissioning artist Hannah Nicklin to produce a ‘social housing’ game which aroused the wrath of the Balfron Social Club and is discussed later in this chapter. For more information, see http://www.socialhousingartsnetwork.org.uk.

[3] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/2015/12/growing-cooking-sharing.

[4] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/2016/06/everywhere-and-nowhere-an-interdisciplinary-postgraduate-symposium-on-imagined-spaces.

[5] See http://www.creativepeopleplaces.org.uk/100-stories-blog.

[6] See http://www.creativepeopleplaces.org.uk/more-than-100-stories/map.

[7] See the project blog here: https://southkilburnspeaks.wordpress.com.

[8] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/2011/07/poetry-hoardings-on-site-in-south-kilburn for images and more information.