Opportunity areas - Part 1: Unearthing socially engaged art’s complicity in the gentrification of Elephant & Castle

Shut-up People's Bureau in Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre

Everyone loves an opportunity don’t they? What about a whole area of opportunities: an Opportunity Area? Investors love them. Property developers love them. Local councils love them. The State loves them. Even (some) artists love them. Opportunities for all! (Well, not people living in social housing … Oh, and not homeless people … Erm, and not market stall holders … Low income families who bought their own council home? No!)

This blog post explores the art world equivalent of MI5 – the socially engaged artists – the creative secret service for third wave gentrification, who, unlike the pioneering, colonial foot soldiers of first and second wave gentrification, do not necessarily live in gentrifying areas and are paid to infiltrate soon-to-be-decanted communities of social housing tenants, low income home owners, market stall holders and small shopkeepers, even, on occasion, homeless people. You see, these socially engaged secret agents work for state and property developer alike and combined in a kind of creative industries public/ private partnership agreement.

Think soft power creative placemaking as reconnaissance, perception management and population pacification. The perfect laughing, cutting, pasting, collaging, film- and model-making, creatively consulting assassins. Popping up here, there and everywhere.

(Well, anywhere undergoing “regeneration” (read: gentrification); anywhere there’s empty shops; anywhere there’s “opportunities” for artists; anywhere that needs to map and document the (so-to-be-past) lives of local communities; to “harvest” their stories; to “capture” memories; TO COLONISE DISENFRANCHISED AND VULNERABLE PEOPLE! Oh, and anywhere that people are willing to pay artists.)

BEWARE!

Socially engaged artists in the pay of the gentrifiers come as sentimental missionaries and amateur cartographers but, like the worst wolves in an Angela Carter short story, the worst artists are hairy on the inside: mercenaries – freelance state agents of social cleansing by participation. They march from Intensification Area to Opportunity Area, from redevelopment site to regeneration zone, from gallery and museum outreach and education departments to Creative People and Places projects; fighting each other all the way; always clawing at doors for another commission.

And so, this blog offers a cautionary tale. A tale with many tails. A tale about several artists who are not unique or unusual but represent complicity with state, local government and corporate interests in the social cleansing of some areas and the disempowerment of others. This is also research. It seeks to begin to lift the lid on how the creative industries works. How networks (spy networks?) are built up and developed. It seeks to reveal that socially engaged art and placemaking are stooges for a sinister neoliberal and neo-colonial system that’s hell bent on exploiting those most in need of help; that thinks nothing of dressing up the marginalising, dispossession and displacement of people in need of social justice, commitment and understanding, not gentrification and social cleansing!

I recommend Brutalism [redacted] - Social Art Practice and You by Balfron Social Club for another take on the invasive nature of social practice art in areas undergoing extreme gentrification.

The blog is in three parts. This is part one. Part two will be published tomorrow and part 3, The Cautionary Tale, will be published on Thursday.

The focus here is on The Elephant and Castle Opportunity Area and the work of three artists who variously collaborated on a range of socially engaged art projects at the Elephant and Castle, London from 2007 onwards: Eva Sajovic, Rebecca Davies and Sarah Butler.

But first a little background. I highly recommend anyone interested in reading about the gentrification of Southwark and the role of artists as both gentrifiers and anti-gentrification activists to take a good look through the Southwark Notes website.

The Elephant and Castle is in the London borough of Southwark – an area undergoing intensive regeneration and gentrification that arguably began with the creation of Tate Modern at Bankside, described as “an important part of the gentrification” of South London (Stallabrass, 2006 [1999], p. 201). The shopping centre at Elephant and Castle is due to be demolished and replaced with luxury housing with new up market shops; it is a classified “Opportunity Area”[1]. The neighbouring Heygate Estate has already been demolished and work on building Elephant Park – another primarily luxury housing development – has already started. The nearby Aylesbury Estate – another large area of social housing – was due to be demolished but has been granted a reprieve at the time of writing, although Southwark Council are fighting the government who blocked the demolition on human rights grounds in October 2016. Clearly, Southwark is a highly contested area in which gentrification is driving uncertainty, dispossession and displacement; in effect, social cleansing.

It is within this context that Sajovic, Davies and Butler have chosen to work. It is, however, questionable whether they are working for the community, for the local council and property developers, or for themselves.

Let’s take a quick look at how the artists describe their practices. Sajovic describes her work as a “socially engaged, participatory practice” working primarily “with marginalised communities or those affected by processes of change” and “in collaboration with the subject” to reveal “personality through images and words as a counter to negative social stereotypes” (Sajovic, 2016). Rebecca Davies considers herself to be “an artist working within a participatory practice through illustration, performance and event”[2] (Davies, 2016). Sarah Butler works on projects across the UK as UrbanWords, describing her practice as exploring and challenging the “relationship between creative writing and place-making” (Butler, 2016a). She also manages A Place For Words, an Arts Council England funded website that “brings together case studies, articles and ideas about how creative writing relates to place-making and regeneration” (Butler, 2016b). She has an extensive list of clients[3], is an experienced public art consultant[4] and is an accomplished fundraiser[5].

Now let’s look at the socially engaged art projects the artists have been involved in.

Sajovic and Butler began working in the area in 2007, when they began Home From Home: Documenting lives through the Regeneration in Elephant and Castle – a project funded by Southwark Council that culminated in a book of the same name (Butler, 2010). The artists described how “Things are changing down the Elephant” and expressed their hope that the book “captures the reality and the magic of the area at the beginning of the twenty-first century” (ibid.). Their choice of words is telling: non-descript, non-judgemental – “change”, “reality” and “magic” at the start of a new century. The stories in the book are sentimental, often conveying a sense of loss but also of hope, of escape. This is unsurprising given that the project was funded by Southwark Council and, arguably, supported (it certainly did not criticise) the regeneration in the borough.

Sajovic and Davies then produced Studio at the Elephant (also funded by Southwark Council), creating a studio in an empty shop in the Elephant and Castle shopping centre for three months during 2011 (Sajovic & Davies, 2011). The residency featured a mix of conversations, exhibitions, workshops, events, screenings and open studio days. It featured some more critically engaged work than the aforementioned projects. Sajovic and Butler also produced Collecting Home an Arts Council England and Southwark Council funded project that collected stories and objects from people living around The Cuming Museum in Walworth in 2012. People were asked to bring in objects “from their own lives” which were exhibited alongside the Home From Home exhibition in the museum (Sajovic & Butler, 2012a). Interestingly, Collecting Home was produced with a number of partners including Hotel Elephant (an arts organisation associated with gentrification) (Sajovic & Butler, 2012b).

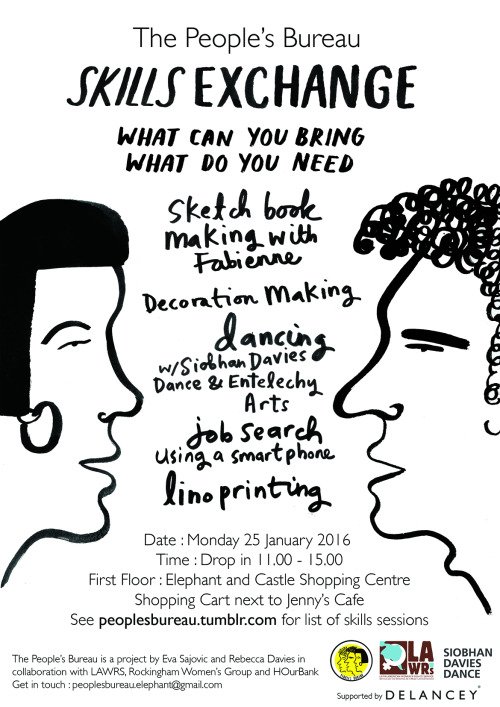

Then, between 2014 and 2015, Sajovic and Davies produced the People’s Bureau project which was funded by Arts Council England, Tate Modern and Elephant and Castle shopping centre developer Delancey. The project is described as “an installation in the Elephant and Castle shopping centre” that held regular workshops to enable “skill exchanges between individuals from local communities” with the aim of making “visible the diversity of cultures, skills, networks and resourcefulness present in an area that is currently undergoing large-scale redevelopment” (Sajovic & Davies, 2016). They described their work as a “socially engaged participatory practice” that sought to “examine/ push the boundaries of collaborative working” by “inviting the community to suggest and co-design activities that they want to engage in” (London Living, 2015). They said the project was “an opportunity to hear and record the voices that create the area as it is now, thus creating a document of a particular time and place” (ibid.). They described their project as an attempt to “create a bridge” between “stakeholders, including local organisations, the local council, the developers and the management” (ibid.). The artists believed their project was “based on gift economy” – “a kind of skills bank on a macro level or people’s university, where communities (and through that individuals) that might otherwise not meet, get in touch with each other and engage in an activity with a common goal” (ibid.). Once again the language used is sanguine, complemented this time with a focus on skills and learning. The People’s Bureau became a Tate Exchange Associate in 2016 (Sajovic & Davies, 2016). It will be resident at Tate Modern during 2017 where the artists will host “a programme of exchanges with other Associates and the public” (ibid.).

In 2015, Sajovic and Davies were joined by Butler to work on Unearthing Elephant, an Arts Council England funded project designed to “create new work in response to the demolition and reconstruction of Elephant and Castle’s shopping centre” (Sajovic, et al., 2016). Employing “research, conversation, experimentation and play”, the artists sought to “engage with residents, traders and visitors” to produce a rather lengthy list of outcomes: “Explore the everyday practices of the shopping centre, with a focus on informality and adaptation”; “Ask how the shopping centre exists in people’s imaginations and memories”; “Tell the building’s story over time and within the broader context of Elephant and Castle and London”; “Make visible the shopping centre’s value and ask how its successes in nurturing a community-focused, open-access space might be understood and sustained in the new development of Elephant and Castle”; and “Discover what kinds of conversations and spaces artistic projects can create at a time and in a place of extreme change” (ibid.). The final output was a film and a “co-produced model of the shopping centre” (ibid.). The idea of creating a model of the old shopping centre seemed sentimental or insensitive or, perhaps, both. The property developer Delancey, of course, use People’s Bureau as a shining example of their commitment to the very community they are in the process of decanting and displacing.

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVPWF8lSsQI&w=854&h=480]

The three artists also took part in Opportunity Area in June 2016[6] – an event that sought to explore “Elephant and Castle and its labelling as an ‘opportunity area’” with other panel members (ibid.). The event was part of the London Festival of Architecture[7] and fed into Dreamers or Builders?[8] another festival event organised by Rebecca Davies that explored how “the arts are being employed by developers to deliver community engagement and ‘consultation’” (London Architecture Diary, 2016). Opportunity Area sought to “critically reflect” on the artists” involvement in the regeneration of Elephant and Castle. They asked four questions: “What is the role of art versus the role of activism? Can they coexist or do they threaten/contradict each other?”; “What tools and strategies do we need in order to communicate the voices and experiences of local people in order to have an impact on the change? Is there a way of working together with others to achieve this? Are there other successful models that we can look to?”; “What is or might be our role now? Do we need/ want to change our position?”; and “How can we negotiate the issues of funding and influence in relation to our work in Elephant and Castle?” (ibid.). The artists describe the discussion as “rich and wide-ranging, with a focus on the ethics and negotiations involved in being funded by, and attempting to positively influence those in positions of power (in this case the developers involved in the regeneration scheme)” (ibid.). They summarised their answers as follows: “Art and activism … are not the same thing, and one cannot replace the other … [but] they might exist alongside each other, finding moments of connection and ways to strengthen and enrich each other … [and] artists may be able to get access to people and places which activists could not”; “There is power and importance in hosting particular stories and memories. Our ambition is to construct a platform from which people can speak for themselves and self-represent”; “Can we affect more change by working with or by boycotting? We want to occupy and interact with organisations rather than just objecting/ criticising”; “We need to try and establish the rules of the game; the motivation of funders in supporting us, the value of what we are doing for them, and how that may or may not affect our freedom to create new and potentially critical work”; “There is a tension between payment and action. Can we expect to influence and not be influenced ourselves? It is a dirty context, but there are opportunities and possibilities there. Can the arts survive without private funding? How do we decide who we are prepared to be funded by?”; and “Can we trust what is being said, by the council, by the developers?” (ibid.).

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yMPlqC6mVr8&w=854&h=480]

This extensive list of “outcomes” seems rather naïve and clearly seeks “cleaner” ways to work with funders, local councils and property developers rather than boycott or oppose them. As they report: “there are opportunities and possibilities” for artists in Opportunity Areas and in “collecting the Cultural Capital of Elephant & Castle”[9] (ibid.). The language of colonisers – mapping, collecting, documenting, exploring, discovering – the cultural pioneers of gentrification. The actions of artists responding to new opportunities. Yet the artists’ desire to “communicate the voices and experiences of local people” is, I argue, a clear indicator of privilege – the privilege of the artist and the privilege of complicity. Speaking for and representing “the community” can be considered as an act of “othering” less privileged people. Leslie Kern describes how this process tends to create simulacra; reorganising everyday community life into “specific temporal landscapes” that exclude, marginalise and render invisible “certain community members and their needs” (2016, p. 442):

The inability of some to participate in the new temporalities of the neighbourhood becomes a barrier to recognition, belonging and representation, one that both hides and enables the “slow violence” of gentrification (ibid.).

I argue that socially engaged art in areas undergoing gentrification is always fraught with risk but it cannot avoid complicity when working alongside property developers, local councils, and state-backed funders, as is the case in the Elephant and Castle, discussed here. Opportunity areas offer artists willing to be instrumentalise chances to profit, advance and progress from favourable situations. Perhaps for excluded and disenfranchised community members, antonyms are more appropriate: misfortune, adversity, prejudice, threat, risk, bad luck, dead-end, and barriers, spring to mind.

Tomorrow, we will examine other “opportunities for the taking” as we explore some of Sarah Butler’s work elsewhere: in Kilburn, for the Social Housing Arts Network, and for Creative People and Places. The opportunities keep flowing as “regeneration” and “placemaking” activities dance in an ever-tightening embrace…

[1] “Opportunity Areas are London”s major source of brownfield land which have significant capacity for development – such as housing or commercial use - and existing or potentially improved public transport access.

Typically they can accommodate at least 5,000 jobs, 2,500 new homes or a combination of the two, along with other supporting facilities and infrastructure” (Greater London Authority, 2016).

[2] For more of Davies” work, see http://cargocollective.com/rebeccadavies, http://peoplebyrebeccadavies.blogspot.co.uk, www.unearthingelephant.tumblr.com and http://theicecreamvan.tumblr.com.

[3] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/cv/clients-partners.

[4] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/category/consultancy.

[5] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/cv/fundraising.

[6] See http://www.urbanwords.org.uk/2016/06/london-festival-of-architecture-opportunity-area-free-event-monday-6th-june-6-8pm.

[7] See http://architecturediary.org/london/events/6238.

[8] See http://architecturediary.org/london/events/6288.

[9] This was how Sajovic, Davies and Butler described a magazine they produced that sought to collate “all the art and cultural projects which have taken place over the past 50 years” (Sajovic, et al., 2016).