Home is where we start from: Cultural Democracy and Working-Class Struggle

Hill Park Kilties, Jarrow, early 1970s.

I was born and grew up in a town called Jarrow (and in neighbouring Hebburn).

Jarrow was, in the words of the town’s socialist MP at the time of the Jarrow March Ellen Wilkinson, a town that was “murdered”. That was in 1936.

I grew up there in the 1970s and 1980s. The place was devastated. But we still had solidarity. We still had pride. We still had community spirit.

The rasping, chiming sounds and colourful, self-organised sights of our local juvenile jazz bands shines in my mind. I recently met a lady in a town in Durham and we made a connection when we remembered these bands. They were a common sight in working-class towns across the North East of England and beyond. They were part of working-class culture. They were about cooperation and sharing and making sure no one was left out and everyone was equal.

They’ve all gone now. Almost.

They practiced and met in local community centres and community halls. They’ve all but gone now too.

Working-class culture has been systematically, intentionally and savagely dismantled by the British establishment and now we are left with parody and nostalgia and concrete statues and black and white photos in long-forgotten books in libraries threatened by closure and grainy films without a home.

To take away one’s culture, our cultures, is to take away our identity and our pride and our solidarity. To do this and to also take away our homes, our jobs, our ways of living and being together, is nothing short of social cleansing.

What little democracy our forefathers and foremothers struggled so long and so hard to get – to be given – is now in danger of being eroded and taken away. Social cleansing is part of this process.

And I, for one, will not see those privileges and rights stolen now. We must think of our children and their children and their children’s children. We must not only reverse the asset-stripping of our communities and our rights, we must also fight for more rights, for equitable ways of living together, for a better world that addresses all the many pressing issues that face us – all of us!

The struggle for cultural democracy is part of our fight back against those who have always sought to keep us down – who have always told us: “KNOW YOUR PLACE!”

I know my place: it’s called HOME. We all have homes of one sort or another. And home is where we start from. Not art galleries or spectacles or museums or whatever else we are told are “cultured” places. HOME. This is the place where we build our own cultures, our way.

As a co-organiser of the Movement for Cultural Democracy and a working-class community artist and art historian, I understand how the British state has always privileged some art forms over others; how it classifies some things “art” and other things “not-art”; how it decides on what is and what is not cultural and therefore “cultured”.

The clue is in the establishment’s firm commitment to “great arts and culture” and “excellence”. These terms (along with others) enshrine privilege and connoisseurship in the hands of the few; in the hands of an elite. They decide what is “great” and what isn’t. They are the guardians of “excellence”. Working-class people and people from anything outside their narrow, white, male-dominated, able-bodied, straight, Christian, middle-class cultural strata do not have a say.

The state uses these definitions to determine how tax-payers’ and lottery players’ money is “invested”. It decides on “cultural blackspots” and areas of “low cultural engagement” solely based on its previous investment decisions and on what it considers to be activities, practices and creative acts that are worthy of the term “art”, “culture”, etc. Its agents and its institutions reproduce these assumptions. And when it invests in places lacking in “cultural capital” it offers much too little, much too late. It also misjudges and belittles the many cultural and creative activities that already exist in these places of “low engagement”. Usually, but not always, it seeks to “civilise” these “uncultured” places and people by preaching the Gospel of Great Art and Culture from its Bible of Artistic Excellence.

This is how our current system operates. This is the preservation of elite arts and culture with a scattering of a sense that this vision of arts and culture needs to be democratised (the democratisation of arts and culture). The “democratisation” process is, at least for those at the top of the hierarchy, a sham, of course. For others lower down the Great Art and Excellence pecking order, it is a gift of enlightenment to be delivered to the “great unwashed” with a missionary zeal. For yet others, it’s a way of making money as mercenaries.

This is a fundamentally hierarchical system that suppresses, represses and oppresses working-class people and “others” people that do not fit their middle-class norms. The state we’re in is as far away from a cultural democracy as is possible to get. We have a representative democracy that ultimately is part of the monarchy. Hierarchy lies at the very heart of our way of being. We are told to participate but the level of permitted participation (a troubling word anyway) is always dictated from above. We are told to collaborate, but collaborate with whom and for what and whose purpose? Cooperation, solidarity, honesty and trust are in short supply.

It is time to wake up to what state-supported arts and culture looks like in 2018. It reflects the deeply unfair and oppressive system in which we live today. It is deeply privileged and hierarchical and it demeans any cultural forms that do not fit with those of the status quo – the elite. This isn’t new. It has always been this way.

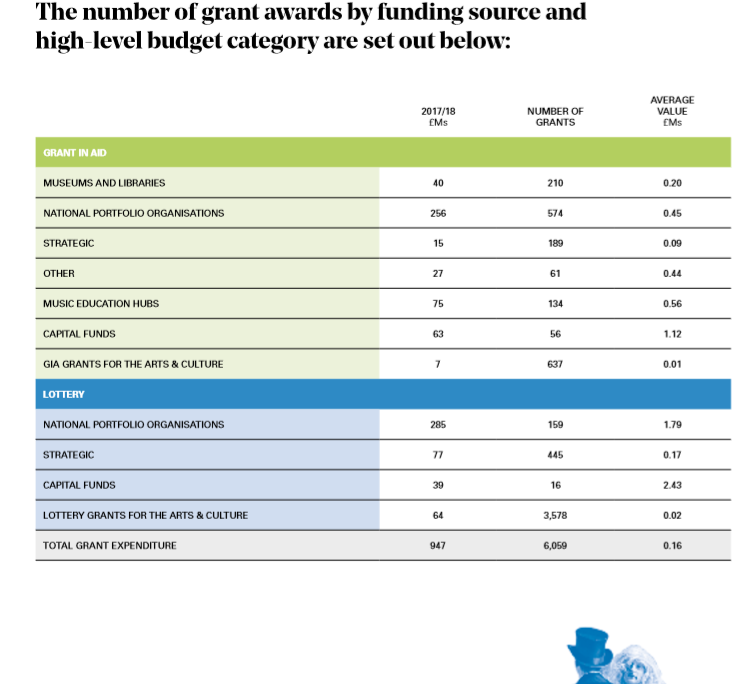

Just look at these statistics from Arts Council England’s 2017/2018 Annual Report.

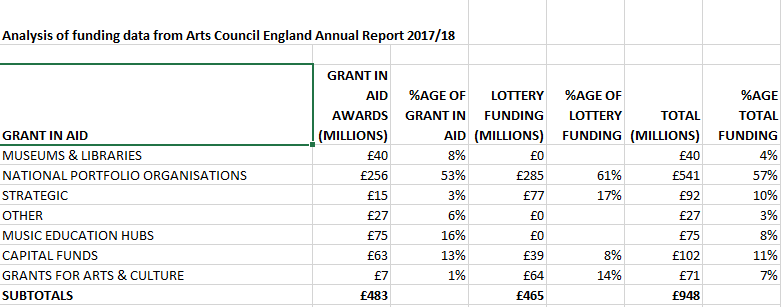

I’ve analysed this data to show percentages of funding allocated against Arts Council England’s own investment categories.

Of the total funding available to Arts Council England, National Portfolio Organisations received 57% of Grant in Aid (money from tax-payers) and 61% of Lottery Funding. They also accessed significant amounts of the National Lottery funding available via Grants for the Arts.

Grants for the Arts – the fund available to individuals, small groups, etc. but also to National Portfolio Organisations and larger cultural institutions – received only 14% of National Lottery funding available to Arts Council England. In terms of Arts Council England’s overall expenditure, Grants for the Arts represented only 7% of its total investment in arts and culture in 2017/18. 93% of funding for arts and culture was not available for those at the bottom of the cultural ladder: a ladder already missing many rungs – rungs that are cultural activities not deemed so by Arts Council England.

This shows why a radical redistribution of funds is urgently required and why we need to work towards a cultural democracy. Why should certain artistic and cultural forms be privileged at the expense of others? Why should a privileged middle-class cultural hierarchy take so much money from not just lottery funds but also from central government coffers? Surely, we should be supporting those most in need in this country, not those with the most? Of course, an equitable and proportional balance of cultural activities should be achieved so that working-class cultures and cultural activities receive their fair share of money available. How this money should be used should be decided upon locally and by fair, transparent and accountable means supported by participatory democracy.

Because the problem is much more serious than these figures suggest. Of the 7% of government funding available to artists, community members, small groups, and arts institutions of all sizes via Grants for the Arts, a huge proportion of the £71 million allocated in 2017/18 went to institutions, rather than artists or other non-constituted groups. This needs fully analysing but looking through the quarterly data provided by Arts Council England shows clearly who gets most.

What we see in England (and I am confident that this is reproduced in relatively similar ways in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) is the almost total institutionalisation of arts and culture.

There’s no money for community groups to collectively organise their own cultural activities. There’s no money for self-organised carnivals, festivals, juvenile jazz bands, and the myriad of other cultural activities not deemed to be worthy of government assistance, should they want it (they may not of course, and that’s fine). There’s little or no money from local councils cut to the bone by imposed Tory austerity. There’s no democratic decision-making for local people. There’s no cultural democracy.

This must change, and it must change NOW!