Live the Dream: A review of this year's British Textile Biennial

As part of my work as critical friend for Creative People and Places project Super Slow Way, I decided to spend two days exploring as much of the festival as possible. My review focuses on what were, for me, the stand-out exhibitions and explores why it felt like the British Textile Biennial felt like two festivals in one.

BRITISH TEXTILE BIENNIAL REVIEW

People queuing to see the Adidas Spezial exhibition at Blackburn Cotton Exchange.

Super Slow Way have spent a great deal of time this year preparing for the British Textile Biennial. I decided to spend two days taking in as much of the festival as possible. The biennial was a really inspiring experience, but I was left wondering if it was yet to find its own identity as I experienced what felt like two biennials running concurrently. I will talk about what I felt were the exceptional elements of this year’s festival rather than critique other elements specifically.

I saw:

· Adidas Spezial Exhibition, Gary Aspen at Blackburn Cotton Exchange

· Transform and Escape the Dogs, Jamie Holman at 50-54 Church Street, Blackburn

· T-Shirt: Cult, Culture, Subversion at Blackburn Cathedral Crypt and Prism Contemporary, Blackburn

· Community Clothing, Aaron Dunleavy at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery

· Katab (Quilting Stories) at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery

· Material, Eggs Collective at Accrington Market Hall

· Mr Gatty’s Experiment Shed, Claire Wellesley-Smith at Elmfield Hall, Gatty Park, Accrington

· Thread Bearing Witness, Alice Kettle at Gawthorpe Hall, Padiham

· Strands of Place and Time, various artists at Gawthorpe Hall, Padiham

· Hidden Gems, various artists at Gawthorpe Hall, Padiham

· Girl Fans, Jacqui Massey at Burley Mechanics

· Art in Manufacturing, Anna Ray, Daksha Patel and Raisa Kabir at Queen Street Mill, Burnley

· “I Believe I Have Seen Hell and It’s White”, Reetu Sattar at Queen Street Mill, Burnley

· Heirloom, various artists at Queen Street Mill, Burnley

· The Mr X Stitch Guide to Cross Stitch, Mr X Stitch and various artists at Towneley Art Gallery and Museum, Burnley

· Banner Culture, Pendle Radicals at Northlight (Brierfield Mill), Brierfield

I did not see:

· The performance of Material, Eggs Collective at Accrington Market Hall

· Suffrajitsu, Horse and Bamboo at Burnley Youth Theatre and The Garage, Northlight, Brierfield

· Any of the talks and workshops

Whilst it was quite clear that the festival was a resounding success, there are opportunities for it to develop to become even better and, in so doing, help the communities along the Liverpool to Leeds Canal develop alongside it. This area of Lancashire is renowned for its textile heritage, so siting the British Textile Biennial here is an incredibly important recognition of this past.

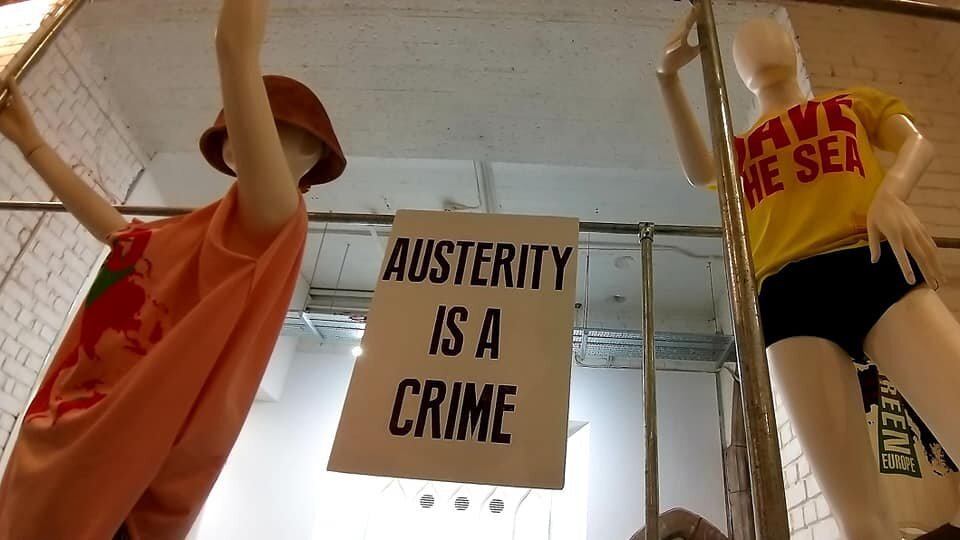

Banner Culture at Northlight, Briarfield.

The Banner Culture show was certainly impressive. Set in a now abandoned textile mill in Briarfield, the multitudes of banners filled one of the large workshop spaces with an array of political and personal messages. Pendle Radicals have done a superb job of attracting so many new and old banners to be displayed in the mill. It is impossible to feel anything other than the emotions of those who carried and still carry such banners on marches when you enter the space. Walking through the lines of banners, each unique, all proud, was powerful. The voices of the people who made them, marched with them, carried them, whispered in the cavernous mill space. There was an eerie peace around the place.

But, the radical messages of the banners and their makers and marchers seemed somewhat at odds with the space. The mill was once the where working-class people made their hard-earned, sometimes deadly livings. Now it has been rebranded as Northlight – a luxury public-private partnership development. How long after the banners return to their various homes and perhaps are paraded again on our streets will it be before the space and the crumbling but still proud mill becomes (in the words of the developers) “the best of both worlds - city living in beautiful Lancashire”? The space that played host to the Banner Culture exhibition is destined to be subdivided, along with the rest of the mill building, into 85 luxury apartments.

Interestingly, the development is described as being in Pendle, rather than Brierfield. Its target audience is commuters to Manchester and beyond, and also buy-to-let investors seeking to rent out luxury apartments to wealthy UCLAN students. It is not a good sign when developers point out that “Burnley is the ‘flipping capital’ of Britain - almost one in 10 homes sold multiple times in just one year, showing the price growth opportunity”. What will this development mean to the people of Brierfield? Can openly promoted asset flipping bring prosperity to them? Unlikely. Brierfield suffered like so many towns along the Leeds and Liverpool canal when the mills and ancillary industries ceased to operate. The town is one of the most deprived places in the country. Does it need a Northlight? What role does Banner Culture play in challenging this profit-focused luxury development? Does it, in fact, support it, adding a much-needed cultural credence to the redevelopment? Nevertheless, the exhibition was one of the high points in this year’s BTB.

Still from I Believe I Have Seen Hell and It’s White, Reetu Sattar at Queen Street Mill, Burnley.

Reetu Sattar’s I Believe I Have Seen Hell and It’s White was a hidden gem. Tucked away behind neutral sack cloth screens, in a corner of Queen Street Mill in Burnley, a film played in a dark corner. Reetu’s film was made in Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh. It presents manual labour – the shredding of cotton by hand – as a beautiful dance. It resulted from the artist’s time spent with Burnley’s Bangladeshi community in July this year. It was unclear how much influence the local Bangladeshi community had on Reetu’s film, but the film was certainly mesmerising. However, it felt like the film could easily be missed by many visitors. Indeed, the other exhibits at Queen Street Mill were also sited in rather odd locations and rather poorly curated. Furthermore, the receptionist and mill volunteers were not particularly enthusiastic about the British Textile Biennial exhibits. Their advice: “just walk about and you’ll come across them”. It felt as though, the mill did not apply the same level of respect to the works as some of the other venues.

T-Shirt: Cult, Culture, Subversion at Blackburn Cathedral Crypt.

T-Shirt: Cult, Culture, Subversion was exhibited at Blackburn Cathedral Crypt, with items deemed a little too risqué for the cathedral shown at the nearby Prism Contemporary. It was a fascinating insight into some of the almost infinite examples of how the ubiquitous t-shirt has been used to convey subversive and humorous messages over the years. It was very well presented, especially in the crypt, and it felt like a powerful intervention. This is, of course, interesting because the t-shirts on show were not only representative subcultures, they were also deeply commercial – whether as high fashion or as counter-cultural status symbols. This show was, like the Adidas exhibition, an intriguing clash of fashion as art, and art and fashion and design as consumerism. For me, the exhibition, dominated by the likes of Vivienne Westwood and Katherine Hamnett, made clear the important impact of capitalism and consumer culture on our everyday lives, bringing to mind Dick Hebdige’s seminal text Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979) which describes how attempts to challenge the establishment often become symbolic forms of resistance (in this case t-shirts) before being appropriated by the establishment and commodified. At the British Textile Biennial, the garments become art objects, cementing their status as historical relics of a cat-and-mouse game of subversion and consumption.

Close up of stained glass window installation, part of Transform and Escape the Dogs, Jamie Holman at Church Street, Blackburn.

Jamie Holman’s Transform and Escape the Dogs exhibition was another stand-out show at this year’s British Textile Biennial. It was presented in an empty shop on Blackburn’s Church Street. The exhibition was the culmination of Jamie’s work as the biennial’s artist in residence. Bespoke banners made by the famous Durham Banner Makers, a stained glass window made by Clitheroe-based Lightworks, an acid house vinyl twelve inch produced by Joe Fossard, Alan Outram and Mia Wilson, alongside installations, film and more, told a tale spun from Pendle witches and hares to hand-loom poets and local blacksmiths, turned painters, and Blackburn’s "Local Films For Local People" filmmaking duo Mitchell and Kenyon to ravers and football casuals. Jamie likes to work collaboratively, and this show certainly brought together a vast array of themes and makers and people with stories to tell.

The show was busy, with people coming in clutching Adidas bags containing the limited-edition Adidas Blackburn SPZL trainers. People reminisced about past rave scenes and lives spent on the football terraces. The banners merged textile pasts with motifs celebrating Blackburn Football Club, Mitchell and Kenyon’s “Wild West” films – now recognised as the first of their kind, and the town’s warehouse rave scene. Light box installations loudly proclaimed “HOPE” and “JOY”. The exhibition text began as follows:

Disenfranchisement creates dissonance.

Dissonance inspires gatherings.

Gatherings initiate transformation.

Transform and Escape the Dogs seamlessly stitched a seam that joined together the stories at the heart of the area’s struggles against persecution and oppression – a story spanning hundreds of years, from the Early Modern period through to the twenty-first century. The exhibition had a nicely curated aesthetic with an accessible feel. It was clear that this was the most original exhibition presented at this year’s biennial, although this is unsurprising, given that Jamie was its resident artist. As an ex-raver (can you ever be an ex-raver?), I felt a real connection to this exhibition and, clearly, the other visitors did too. Nevertheless, there it had a rather nostalgic feel which was, however, unsentimental.

Close up of Mr Gatty’s Experiment Shed installation, Claire Wellesley-Smith at Elmfield Hall, Accrington.

Mr Gatty’s Experiment Shed saw Claire Wellesley-Smith, with the help of another artist, transform the dilapidated brick building in which the dye-maker and industrialist F.A. Gatty produced new techniques for making dyes for the British army: particularly Turkey Red and Khaki. The shed had been reanimated using video projections, atmospheric lighting, glass vials and audio effects. The experience was surreal and moving, immersing you in a reconstructed version of Mr Gatty’s world. It would be great to see the installation become a permanent feature at Elmfield Hall. It would certainly help support any future bids to the Heritage Lottery Fund to develop the site and build on the excellent research undertaken by Claire and a superbly knowledgeable and very dedicated team of volunteers. The team have developed over more than a year during Claire’s weekly participatory workshops as part of her Local Colour project for Super Slow Way. There had been a drop-in printmaking workshop the day I visited too that had encouraged visitors to try out various techniques. The attention to detail and the exceptional knowledge of the artistic team and the volunteers here was outstanding – very different from some of the other shows in the museum venues.

Close up of trainers at Adidas Spezial exhibition at the Cotton Exchange, Blackburn.

The stand-out exhibition of this year’s British Textile Biennial was undoubtedly the Adidas Spezial show at Blackburn’s Cotton Exchange. Queues stretched down the street. People queued inside patiently. More than 1,200 pairs of limited-edition Adidas trainers were immaculately presented inside large polytunnel-like structures inside the rather decrepit interior of the town’s once iconic Cotton Exchange. The building has been saved and bought by a community group who are now seeking to renovate the building and return it to community use. Thousands of people came to see the show and buy some trainers.

Speaking to Jamie Holman, it became clear that Adidas had taken the event very seriously, the company had paid staff and offered volunteers free trainers for helping. Adidas also organised two free music events featuring Goldie and Primal Scream. Jamie and the Super Slow Way team had been concerned about how I might react to the inclusion of an obviously commercial exhibition in the biennial. I consider it to have been a masterstroke that was perfectly in keeping with the biennial’s theme of “The Politics of Cloth”. It brought huge numbers of people who would never have otherwise attended the biennial. It did this by enabling people to indulge in their passion for trainers. Many of the visitors were working-class and it is important to recognise that, like people of all classes and backgrounds, consumerism is an incredibly important and deeply engrained cultural practice. I was in awe of the vast array of trainers and the animated way that people studied and talked about the classic styles on display. People were carrying Adidas bags all around the town. The show generated a real buzz! It is easy to say that there should be no place in UK “art and culture” for an exhibition-cum-sales event that celebrated trainers, but to do so is to become elitist. One of the longest-running icons of consumer culture is the trainer; another the t-shirt. Like football and raves and pubs and fashion and tattoos and nails and hair styles and a myriad of other now deeply consumerist activities, they are important elements of our everyday lives. They are perfectly ordinary forms of personal and collective expression that are, for me, just as valid as visual art or a trip to the theatre or opera or other forms of officially recognised “culture”. This exhibition proved it.

The British Textile Biennial was undoubtedly a resounding success, with significant national and local press recognition, and yet, it felt like there was almost two biennials: an adventurous and well-produced biennial featuring the exhibitions discussed here plus a substantial amount of other work that was often less well presented and sometimes less well produced. The “museum” settings of Gawthorpe Hall, Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery, Queen Street Mill and Towneley Art Gallery and Museum felt disconnected from the exhibitions mentioned here and were, with the exception of Alice Kettle’s Thread Bearing Witness at Gawthorpe Hall, often oddly located, curated and/or lacking sufficient invigilation.

It was clear from a brief conversation with the Super Slow Way team that they had found it difficult to fully utilise their group of volunteers on occasions. A festival of this scale, over such a large geographical area, needs coordinated, relatively self-sufficient volunteers supported by paid staff. This requires considerable planning, recruitment and selection, and management. It might be necessary to build a team earlier and give them more responsibilities and a greater role to play in the pre-festival planning and production. This would enable the volunteers to get more out of their experience and would enable them to mirror the passions of the artists and biennial team so evident this year.

I left feeling that the British Textile Biennial was yet to feel comfortable about its identity and also entrusted its identity a little to frequently and easily to others who did not pay it the respect it and the work it displayed deserved. The “odd” locations definitely worked best, and this is perhaps a lesson to be learnt for future iterations. The passionate work undertaken by Jamie Holman, Claire Wellesley-Smith and her volunteers at Gatty Park, the Pendle Radicals, and the Super Slow Way team in putting together the biennial was clear. I witnessed the pre-show preparations for Egg Collective’s Material at Accrington Market Hall, and it was clear that the performance and the location would again be a stand-out event. I didn’t get to see Horse and Bamboo’s Suffrajitsu during the biennial but, having seen it last year, I know it will have been a resounding success.

Perhaps the 2021 British Textile Biennial can really explore unusual spaces of the sort mentioned here and also take place more in the street and other public places and spaces? In terms of identity, it may be necessary to develop the sort of passionate and original programming mentioned here, whilst offering other venues, organisations and groups the opportunity to develop their own “fringe” programme around that core.